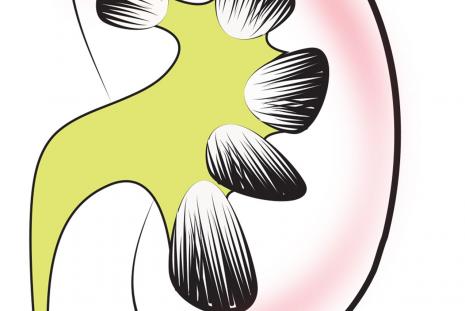

Chronic kidney disease is a condition that occurs when a person’s kidneys are damaged and can’t remove harmful waste from the blood. This can lead to high blood pressure and severe infections. The disease affects about 13.4% of the population globally. Around 1.23 million people died of chronic kidney disease in 2017.

But this doesn’t have to be the outcome. Patients can be treated with dialysis to mechanically remove the waste material and excess fluid from the bloodstream. Or they could receive a kidney transplant to replace the damaged kidney. Patients and their caregivers can also minimise the symptoms by carefully managing what they eat and drink.

For dialysis to succeed, it’s important to prevent overloading the kidneys. There is convincing evidence that following a healthy diet may lower the risk of disease complications and allow patients to live well despite having the disease.

The recommended diet involves keeping salt intake below 5g per day because damaged kidneys can’t excrete sodium very well. Retaining sodium in the body leads to fluid overload, which is bad for blood pressure and vascular health. Excluding table salt from the diet is a challenge for many patients, though.

It’s also important to reduce potassium content in food, because damaged kidneys aren’t good at excreting excess potassium in urine. Too much potassium can weaken the heart muscles, leading to irregular heartbeat and heart attack. One way to reduce potassium in the diet is by boiling vegetables and discarding the water.

Consumption of red meat is restricted as it leads to accumulation of toxic substances in the body. Patients can eat poultry and fish instead to get animal protein, but this may be expensive. Poor consumption of protein is likely to expose patients to malnutrition, which is a common feature in patients on dialysis.

Kenya has seen an increase in the number of patients undergoing dialysis. This is mainly because the service has become more widely available. We conducted a study with patients on dialysis to understand what factors influence their compliance or non compliance with dietary prescriptions for patients with kidney disease on dialysis.

Understanding why it can be hard to follow the diet allows health practitioners to work with individual patients in finding solutions.

Challenges with renal diet prescriptions

The recommended diet can be difficult to follow because patients and caregivers find it complex. And at times it may seem to contradict ideas about healthy eating, cultural norms, social functioning, and individuals’ sense of control.

We found that almost all participants (92.8%) in our study were aware of the dietary recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease, but most of them were not following it. The main source of their information was the nutritionist (90.3%) at the health facility. More than half (61.8%) of them, however, had challenges in following the diet recommendations. Most of them considered the recommendations to be important, with health benefits. But 83.8% felt that the diets were restrictive and did not fit with their other ways of eating.

The main problems with the diets were the prescribed food types, preparation methods and sharing meals at social gatherings. Sometimes patients couldn’t avoid certain types of restricted foods, or the prescribed foods were costly or unavailable. Also, caregivers found it stressful, time consuming and expensive to prepare separate meals for the patient and other household members.

Respondents also said it was no longer possible to eat the foods they were most familiar with such as fried food, food with salt added, or locally accessible fruits like bananas or oranges. They couldn’t share family meals, or eat away from home because the foods served are what they are not allowed to eat. They sometimes withdrew from social gatherings for fear of explaining to people why they were avoiding certain foods.

A number of households were also constrained by the high cost of prescribed fruits, vegetables and white meat (chicken or fish) as well as cooking separate foods for the family.

About 39% of participants therefore found it difficult to give up certain foods and drinks. They considered renal diets unpalatable without salt, sugar, or cooking oil. They knew they should be eating boiled vegetables but found these didn’t taste good, or the cooking method seemed to contradict their idea of healthy food. Therefore, most were likely to consume food high in potassium, preferring not to eat food that had no taste and was less nutritious as the vitamins C and B-complex are removed in the preparation.

We observed that consuming unhealthy restricted foods that are palatable and affordable was common among more than half of the patients. This puts them at risk of disease complications, making dialysis less effective and increasing their risk of death.

Studies in developed countries have similarly found that more than half of adults on dialysis do not adhere to their diet prescriptions.

Way forward

Nutritionists and dietitians can help patients by prescribing a more flexible, affordable, palatable, and nutritious diet. Patients should be involved in developing local recipes based on natural, locally available, and affordable whole foods that contain natural flavours and do not require additives.

To overcome nutrient loss, a variety of locally available vegetables and fruits with lower potassium and sodium content but high vitamins C and B-Complex should be encouraged.

Nutritional advice in chronic kidney disease is based on nutrient requirements linked to published evidence and guidelines. Where international guidelines are the main source of advice, development and use of national guidelines based on locally available foods should be a priority. A good starting point in Kenya would be developing local renal nutrition guidelines, which are currently lacking, based on the most recent, updated National Food Composition Database.

Author: Dr. Rose Okoyo Opiyo, Lecturer, University of Nairobi, School of Public Health.

This article was originally published on The Conversation